Bodecker

Bodecker Bodecker

Bodecker

Any resemblence to real life is no coincidence in this

true story about one of America's nicest families...

written by the man who is both father and mother

to a band of lively boys

by Everett G. Reid

WHEN my five foster sons, ages seven to thirteen, gather around the table, the food goes down like rain water into a storm sewer.

Sammy (thirteen and absent-mindedly in love with someone or something most of the time) finished his macaroni first, probably because he has had the most experience with chewing and swallowing, and yelled loud enough to be heard over the usual arguments, "Hey, Pop, what's for dessert?"

I had been waiting eagerly for this moment. I went to the kitchen and brought back the cake plate, dishes of ice cream and frosty glasses of pop.

Plumpish Buster (age eleven, never misses one of the dozen odd meals we serve each day) surveyed the unusually abundant goodies with hungry eyes and asked, "Golly, what's the party grub for?"

I hammered on the table for silence – a necessary procedure when the incessant battle is raging hot – and when all eyes were to me, I uncovered the cake with a flourish.

It was chocolate frosted, with rather crude letters in yellow frosting across the top that spelled "Happy Birthday."

Proff (age nine and our scholar) was puzzled. "Whose birthday is it?"

Quick questioning glances passed from boy to boy. Each denied being the lucky party. It was Beans (several teeth missing) who figured it out. "It's Pop's!" he yelled. "That's why there ain't no candles."

Buster, with an eye to the inner man, demanded. "How big a piece of cake can we have?"

Pete (age twelve, family mechanic who makes the TV work when no one else can) was indignant. "Don't you ever think of nothin' but eatin'? Where's your manners?"

"Savin' 'em till I grow up," Buster explained, eyeing the cake.

"Now wait a minute. Hold onto your shirttail. We gotta sing 'Happy Birthday,'" Sammy reminded them.

More or less in unison, but definitely not in key, five young voices shrieked, "Happy birthday to you..."

"How old are ya, Pop?" asked Sammy, his mouth full of cake.

"You shouldn't ask him that," Proff protested, "'cause, when people get old like Pop is, they don't like to think about it, do they, Pop?"

I protested that it really didn't bother me too much yet. After all, I was only fifty-five.

"Golly!" gasped Beans. "That's five years more'n half a hundred, isn't it? How does it feel?"

I assured him it didn't feel bad. Or did it? Suddenly I wasn't too sure. Sammy, who spends a lot of time in adult company and often comes up with their usual clichés, added the crowning touch. Looking me over critically, he remarked, "Well, I only hope that when I get to be your age, I'm as good a man as you are."

I ACKNOWLEDGED the compliment and quickly passed seconds on cake. Eating shut off further conversation regarding my venerable age. There were only the usual arguments over who'd gotten the biggest piece – a matter that gets more consideration around our table than the state of the nation gets in a barber shop.

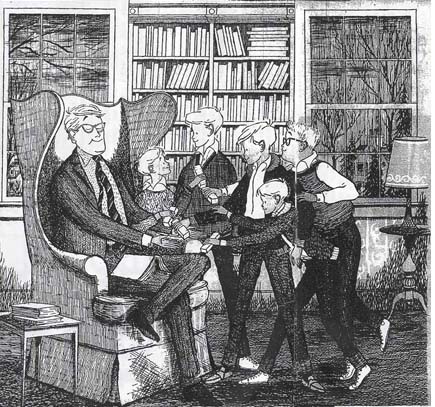

Fog never rises more inconspicuously than my five boys sneaking away from the table to avoid being called on to wash the dishes. Since it was my birthday. I didn't press the matter. And anyone who can't see the justice of my washing dishes to celebrate my own birthday doesn't know how things are done in our household. It is an unwritten rule that I always make a special effort to make everyone else happy on holidays that especially concern me. Dishes finished. I was sitting in my room enjoying my book in that short period of peace that always occurs before the boys decide it is safe to come back and watch cartoons on TV. Hearing the front door open. I looked out and saw them all enter the house, closing the door gently behind them.

Almost on tiptoe, they came to my door and stopped, standing respectfully outside. As per schedule, in such cases, I made believe I didn't see them until I turned a page. Then I made believe I was surprised.

"Well, guys," I asked, trying to look brightly expectant, "what can I do to make you happy?"

Pete, who seemed to be leader of the delegation, asked most politely, "Can we come in?"

They entered and stood in a silent row before me, glancing uneasily from one to another. I kept them in suspense for a little while and finally asked, "Well?"

Pete, with all eyes on him, chewed nervously on his roll of bubble gum, cleared his throat and began, "Well..." stopped, started again, then drooped. "Naw, you wouldn't."

"Wouldn't what?"

"Well..." bravely, Pete began again. "Naw, I know you wouldn't."

"I probably wouldn't," I agreed, and picked up my book.

Proff rushed into the breach, "Hey, Pop, we was wondering if you'd give us an advance on our allowance."

"Naw, he wouldn't," repeated Beans.

"No, I wouldn't," I assured them and picked up my book with finality.

Proff is very dramatic. He can make a three-act production of asking to have the potatoes passed. He clasped one of my hands in both of his, rolled his eyes heavenward, and from the depth of an agonized soul, pleaded, "But, Pop, we just GOTTA have a quarter apiece!"

"Yeah," explained Buster in his lumbering way, "we wanna buy ya ––"

"Shut up!" shouted Pete.

Buster looked at him reproachfully over his thick glasses. "You coulda said, 'Please.'"

Proff squirmed in unbearable appeal. "Pleeeeze, Pop! Pleeeeze!"

At this point I gave my usual speech appropriate to the occasion. It is an occasion that arises with monotonous frequency so I had it well memorized. I explained that debt was slavery, that slavery was a most undesirable condition, and that one was never too young to start learning how to use money.

Beans began to bargain. "We'll wash the dishes."

"They're already washed."

"We'll wash 'em tomorrow."

"For a dollar and a quarter I'll wash them myself."

"All next week?"

So I reached for my wallet.

"Better make it twenty-six," said Pete. "There's a penny tax."

That's another night's dishwashing," I bargained.

"O.K." They were reckless now.

Like leaves before a high wind, five boys burst from the door, mounted their bikes and flew up the road. In a few minutes they were back, dropped their bikes on the lawn and stormed into my room.

"Hold out your hands, shut your eyes and don't open 'em til we say, 'Happy Birthday.'"

I obeyed. One by one, five small packages were deposited in my out-stretched palms. Then they all yelled, "Happy Birthday!" and I looked.

FIVE small articles wrapped in blue drugstore paper lay there. I opened each with the expected gush of admiration. When they were all opened and exposed to view, I gave the boys my well-practiced look of dumb admiration.

"Guys," I said, with a catch in my voice that wasn't artificial, "this is simply wonderful of you. How did you ever think to buy these for me?"

Proff wriggled with happy, excited pride. "We asked the girl in the drugstore, and she said she was sure you'd like them."

Yes, I liked them. Maybe not for what they were, but for the warmth and kindness and thoughtfulness displayed by five small boys who were ordinarily, like all small boys, selfish and thoughtless. Five corncob pipes. I laid them on a shelf near my bed where I can look at them now and then and have my faith renewed in small boys. It's about the only use I can make of them. I don't smoke.

Return to Main Page