RECOLLECTIONS OF A REBEL REEFER

James Morris Morgan 1845 - 1928

1917

CHAPTER XXV

I finally become a passed midshipman--Battery Semmes--The Dutch Gap Canal--Mortar pits and rifle pits--The lookout tower--Trading with the enemy--Pickett's famous division charges a rabbit--A shell from a monitor destroys my log hut--Good marksmanship--An unexploded shell--General Lee inspects battery--Costly result of order to "give him a shot in fifteen minutes"--Demonstration against City Point--Confederate iron-clads badly hammered--"Savez" Read cuts boom across the river--A thunderous night.

SHORTLY after the fall of Fort Harrison I passed my examination for promotion and arrived at the dignity of being a passed midshipman. I was immediately ordered to the naval battery called Semmes, situated on a narrow tongue of land formed by the river. It was the most advanced of our defenses on the river, and was the nearest of any of our batteries to the Dutch Gap canal which was then being dug by General B. F. Butler.

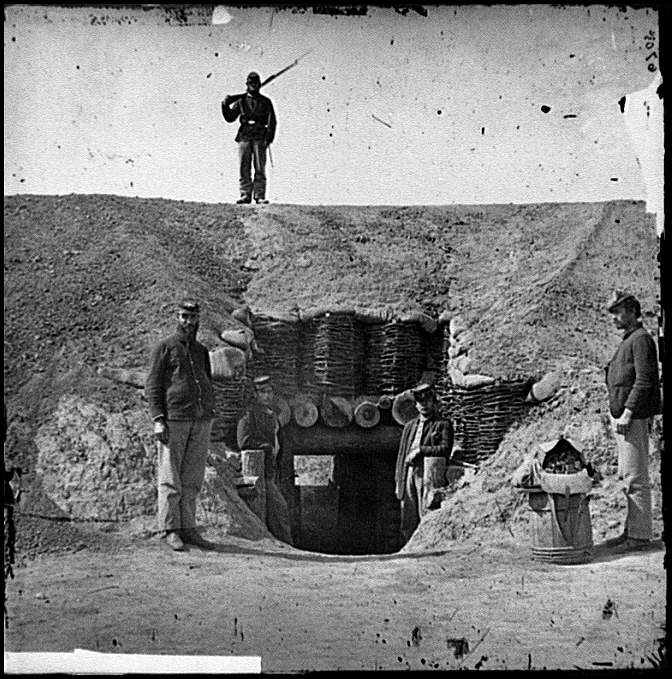

Our seven heavy guns, rifled and smooth-bore, were mounted in pits dug on the brow of a gently sloping hill-- the battery was only thirty feet above the river. Between each of the guns was a bomb-proof which protected our ammunition. The guns were mounted on naval carriages so that our sailors could handle their accustomed blocks and tackles.

On the opposite side of the river, and forming a semicircle around the peninsula on which Semmes was located, were the heavy Union batteries called Bohler's, Signal Hill, Crow's Nest, the Dutch Gap batteries, and the Howlett House batteries, and when they all opened fire at once they made a perfect inferno out of Battery Semmes. It surely was a hot spot.

Some six hundred yards in front of Battery Semmes, on the land side, we had four little Cohorn mortars in a pit, and with these we tossed shells constantly into the canal to interfere with its construction. General Butler put a number of Confederate prisoners to work in his canal, and very thoughtfully sent us word that we were only killing our own men with our mortar shells. About the same time that we received this considerate message, Jeff Phelps, a midshipman who had been one of the "Brood of the Constitution," and who was one of the prisoners compelled to dig in the canal, in some way managed to get a note to us telling us that we "were doing fine" and to "keep it up." We only kept some eight or ten men at a time in the mortar pit and between the pit and our battery were a number of rifle pits. When the mortars aggravated General Butler too much, he would send a force across the river to charge the mortars. Seeing them coming, our men would hastily beat a retreat, and like prairie dogs tumbling into their holes, they would disappear. The Union soldiers would, of course, capture the mortars and spike them, but when we thought that as many of them as the pit could hold were well in it, we would cut loose with the heavy guns of the big battery behind us which were trained on it. Then the Federal soldiers would hasten back to the river, and before they could get across, our men, who were provided with bows and drills, would have new vent holes bored and would be again tossing shells as though nothing had happened to interfere with their day's work. Why General Butler's men never carried off the mortars with them we could never understand--two strong men could have lifted any one of them, they were so small and light.

General Butler had built a lofty lookout tower out of timber. It was very open work, and on the top of it he placed a telescope. I met a member of his staff after the war who told me that they could see every movement we made, and that on one occasion he had distinctly seen a man in our battery cut off a chew of tobacco and put it into his mouth.

There was a mystery as to the way in which privates would come to a tacit agreement with the enemy about not doing any sniping on certain parts on the line. I knew of one stretch of breastworks where our men could expose themselves with perfect impunity up to a spot on which stood an empty barrel, and on the other side of that barrel, if a man showed an old hat on the end of a ramrod, it was instantly perforated with bullets.

The Union soldiers craved tobacco of which the Southerners had an abundance and the "grayback" longed for coffee or sugar. At some points on the line trading in these commodities went on briskly without the knowledge of the officers. Their dealings were strictly honorable. A man, say from the Southern side, would creep outside the works, and when he reached a certain stump he would place a couple of large plugs of tobacco on it and then return to his companions. After a time he would again creep to the stump to find that his tobacco was gone, but in its place was a small quantity of the longed-for coffee and sugar. We always carried one or two long plugs of tobacco in our inside breast pockets, as it was a common belief that if a man was captured and had tobacco it would insure him good treatment.

One foggy night I was on duty and had visited our outposts. While returning to the battery on a path close to the riverside, I distinctly heard oars slapping the water--the rowlocks were evidently muffled. Although I could not see the boat I felt that it must be very near the shore, and I hailed it with a "Boat ahoy! Keep farther out in the stream!" The answer came back: "We don't do any picket firing on this line." I told the spokesman that I knew that, but we didn't want him to bunk with us, and hardly were the words out of my mouth when the bow of the boat was rammed into the mud at my feet. I felt sure my time had come, and hastily jerked my pistol out of the holster intending to fire so as to give the alarm, when I heard a voice say, "For the love of Mike, Johnny, give me a chew of tobacco." The tone was so pleading and earnest that I could not resist it and handed the fellow my plug. In return he gave me a canteen full of whiskey. We entered into conversation, and I discovered that he was an old classmate of mine at Annapolis who had "bilged" and was now a master's mate in charge of a picket boat whose duty was to give warning if our ironclads descended the river. I warned him about the folly of his act, and he shoved out into the stream and disappeared forever out of my life. When I produced my canteen before my messmates they fairly went wild with joy, but nothing ever could induce me to tell how I had come into possession of the liquor.

Muskrats or rabbits, when caught, which was rarely, were a welcome addition to our menu. Pickett's division supported our battery and was encamped about half a mile from us. One day we thought that those thousands of men had gone crazy--there was the wildest commotion among them. Men rushed to and fro in the wildest confusion, falling over one another in every direction--it looked like a free fight. We sent over to find out the cause of the riot and were informed that one poor little "cotton-tail bunny" had jumped out of a bush in the centre of the camp and that some ten thousand men had given chase in hopes of having him for supper.

The winter of 1864-65 was an intensely cold one. Snow from three to six inches in depth lay constantly on the ground keeping the trenches wet and muddy, and the consequent discomfort was great. Lieutenant Bradford, our commander, and Lieutenant Hilary Cenas and the surgeon had two log huts to live in. Becoming envious I got several of the men to assist me in building a cabin for myself, with the chinks all stuffed with mud and with a beautiful mud chimney of which I was very proud. I had had it located in a little gulch behind the battery and it did look so comfortable, but alas, work had gone on very rapidly in the construction of the canal despite our continual mortar fire, and on the afternoon of the day on which my house was finished a monitor fired several eleven-inch shells through the canal, and with the whole State of Virginia to select from, one of these projectiles could find no other place to explode in but my little cabin, which it scattered to the four winds.

Some days there would be a lull in the artillery fire, and we could walk about exposing ourselves to the enemy's fire with perfect impunity, and on other days the most trifling movement on our part, such as the moving of an empty water barrel, or a few men chasing a frightened and bewildered "cotton-tail" would bring upon us a storm of projectiles from the enemy's guns. Constant practice had made the artillery firing very effective, so much so that it was not an uncommon thing for us to have one or more of our guns knocked off their carriages. Lieutenant Cenas seemed to have a tacit understanding with the gunner of a rifled piece in the Crow's Nest Battery whose marksmanship he admired very much. Cenas would go outside of the works and place an empty barrel or tobacco box on top of a stump, and then, stepping to one side, he would wave his arms as a signal to his favorite gun-pointer on the other side, and immediately we would see a puff of smoke and the projectile would always tear up the ground very close to the stump and frequently both stump and barrel would be knocked into smithereens.

One afternoon a monitor fired a shell through the canal which landed a few yards in front of our battery. A sailor, in pure dare-deviltry, went outside to pick it up. Just as he got to it I saw a thread of smoke arising from the fuse, and I yelled to him to jump back--but too late. The sailor gave it a push with his foot and it bounded into the air taking off the man's leg; the shell then landed in one of our gun pits and exploded killing and wounding several men. It must have been spinning with great rapidity on its axis and only needed the touch of the sailor's foot to start it again on its mission of destruction.

We flew no flag, as it was useless to hoist one; the enemy would shoot it away as fast we would put it up. A wonderfully accurate gun was a light field piece, a Parrott gun, which would come out from behind the Bohler Battery, take up a position in the bushes, and shoot at any man bringing water from a near-by spring, and he was frequently successful in hitting him. One day General Lee was inspecting the line and stopped for a few moments at our battery. He ordered us to drive this fellow away, and then looking at his watch added, "Give him a shot in fifteen minutes." Then the general on his gray horse rode away. At the expiration of the fifteen minutes we let go our seven heavy guns into the bushes where we supposed the fellow to be with the result that he limbered up and hastily took refuge behind his works, and from fifty to seventy-five guns in the batteries which enfiladed Semmes cut loose into us and kept it up for three days and nights, dismounting three of our guns, killing and wounding a number of our men.

We could shoot just as well at night as we could in the daytime, as from constant practice we had the ranges of all of the enemy's batteries, and had marked the trunnions of our guns for range and the traverses for direction. Such firing was accurate, as was proved on several occasions by our discovering at daylight that we had dismounted some of the guns of our antagonists.

In the latter part of January, 1865, our supply of ammunition was running short, and as a consequence we were ordered to be sparing with it, so we would only fire a gun when the enemy's fire would slacken up a bit to let them know that we were still there. This seemed to encourage our opponents and they hammered us all day with their big guns, and all through the nights they dropped mortar shells among us. These shells, with their burning fuses, resembled meteors flying through the air; they made an awful screeching noise as they tore the atmosphere apart when coming down before we heard the thud of their striking the ground and the terrific explosion which would follow, and then would come the whistling of the fragments as they scattered in every direction. We were so accustomed to these sounds that we did not allow them to interfere with our slumbers, as wrapped in our one blanket we slept in the bomb-proofs or magazines.

The end of the Southern Confederacy was near at hand, although we at the front little realized the fact. The authorities in Richmond determined to make a daring attempt to capture or destroy General Grant's base of supplies at City Point on the James. Late on the afternoon of January 23, 1865, we received notice to be ready, as our three ironclads, the Virginia Number 2, the Richmond, and the Fredericksburg, would come down that night, run the gantlet of the Federal batteries, and try to force their way through the boom the enemy had placed across the river (at Howlett's) in anticipation of just such an attempt. I happened to be officer of the day. The night was very dark, and suddenly I heard a sentry challenge something in the river. I ran down to the edge of the water and arrived there just in time to see a rowboat stick her nose into the mud at my very feet, and was much surprised to see my old shipmate, "Savez" Read, step ashore. He was in a jolly mood, as he told me that our ironclads would follow him in a couple of hours, and that he was going ahead to cut the boom so that they could pass on and destroy City Point. "And now, youngster," he said, "you fellows make those guns of yours hum when the 'Yanks' open, and mind that you don't shoot too low, for I will be down there in the middle of the river." And then he put his hand affectionately on my shoulder and added: "Jimmie, it's going to be a great night; I only wish you could go with me: a sailor has no business on shore, anyway;" And laughing he stepped back into his boat and shoved out into the stream.

The enemy must have had some information as to our plans, for Read had not proceeded very far before the bank of the river looked as though it was infested by innumerable fireflies as the sharpshooters rained bullets on his boat which was proceeding with muffled oars. They completely riddled it, but Read kept on while bailing the water out of her, and strange to say he reached the boom and successfully cut it.

About two hours after Read left, our so-called ironclads noiselessly glided by the battery. The stillness was unbroken for so long a time that we began to congratulate ourselves that they had safely got by the enemy's batteries without being discovered. But our exultation was premature--they did get by the Bohler and Signal Hill batteries unobserved, but unfortunately the furnaces of the leading boat were stirred, and a flame shot out of her smokestack which instantly brought upon her a shower of shot and shell, and instantly the big guns on both sides were in an uproar. My! but that was a thunderous night; the very ground quivered under the constant explosions.

The next morning we learned that our demonstration against City Point had resulted in a most mortifying failure. The smallest of our ironclads, the Fredericksburg, passed safely through the obstructions, but the Virginia, which steered very badly, ran aground and blocked the passage to the Richmond. The wooden gunboat Drewry also missed the channel and ran ashore. The Fredericksburg was recalled and the big monitor Onondaga with her immense guns arrived on the scene shortly after daylight. With one shot she smashed in the Virginia's forward shield. The Virginia got afloat again and presented her broadside, which was also perforated as though it was made of paper. She then brought her after gun into action and a shot from the monitor also smashed her after shield. They all returned that night under a rain of projectiles from the shore batteries similar to that they had been exposed to the night before, and on that occasion our ironclads, on which we had based such high hopes, fired their last hostile shot. The end was near.

Fort Brady